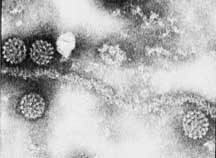

Electron microscope image of HPV particles

The papillomaviruses are a group of

small DNA viruses that infect higher vertebrates; for example, humans,

nonhuman primates, cattle, and deer. These viruses are widespread

in nature and appear to have evolved alongside animals that they

infect.

About 70 different types of virus comprise

the human papillomaviruses (HPVs). These viruses are classified

by scientists as similar or different (from one another) based upon

the genetic sequence that encodes three key viral structures; the

E6, E7 and L1 proteins. All of the human papillomaviruses target

the cells that make up the outer skin, and smooth moist tissues

and mucous membrane surfaces of the body, i.e., the epithelium.

Most HPVs cause small warts or "papillomas"

on the skin surfaces. Some warts may be highly noticeable, resembling

tiny cauliflower that rise above the skin surfaces and rest on very

small stalk-like structures. However, many warts may be flat or

dome-shaped and hardly noticeable to the untrained eye.

Crystallographic structure of HPV capsid (left) and

computer-generated model

Crystallographic structure of HPV capsid (left) and

computer-generated model The virus particle (virion) itself

is small by virus standards (55 nanometers), and it is not enveloped

by an outer membrane coating. Two virus proteins form the outer

protein coat or capsid, the L1 and L2 proteins, which arrange to

form an icosahedron (i.e., 20 sided shape). The viral DNA is double-stranded,

and exists as a circular and tightly coiled structure contained

within the capsid.

The virion infects a cell by binding

to a receptor on the cell membrane, which triggers the cell to engulf

the virus. The virus particle appears to travel to the cell’s

nucleus and "uncoats" itself to begin manufacturing virus

proteins. The "gene products" or proteins that are made

in the host-cell nucleus from the virus DNA have specific tasks,

some of which we understand and others that remain a mystery. The

early made proteins E6 and E7 have been shown to directly disrupt

normal cell pathways to instead promote virus growth, resulting

in abnormal or even cancerous cells.

Unlike many other viruses, the HPV

life cycle is poorly understood because the virus cannot be readily

grown in the laboratory. Current research focuses on interactions

of the various HPV proteins with host cell machinery, as well as

the mechanisms of immune response to viral proteins. The key to

developing successful treatment lies in better understanding the

protective role of the immune system, as well as unraveling the

complex HPV life cycle so as to effectively disrupt it.